Hispanic Activists and Entrepreneurs in Marijuana Strive for a More Equitable Future

Most people know the story behind Reefer Madness and the near century of cannabis prohibition that followed. What’s often omitted from marijuana’s history in the United States, though, is the racist, anti-Hispanic motivation behind banning it.

Before U.S. authorities turned cannabis into a Schedule 1 drug and put millions of people in jail for using it, the plant was a popular medicine found in at least a half-dozen pharmaceutical compounds during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

By 1910, unrest in Mexico during the Mexican Revolution forced thousands of people to immigrate north. With them, these new U.S. residents brought their native language and customs— one of which was smoking cannabis to relax.

The Mexican immigrants called their plant “marihuana.” Americans knew about cannabis, but few understood the Spanish name for the plant. They didn’t realize marihuana was something they already had in their medicine cabinets.

When the media began to capitalize on public fear of “disruptive Mexicans,” Americans started associating their new neighbors with a host of other stereotypes. They labeled the new immigrants alcoholics and thieves who now also smoked this harmful, exotic plant.

Stigmatizing cannabis was just another way for American cities to vilify newcomers to the country – just like San Francisco had done decades earlier by outlawing opium to manage an influx of Chinese settlers. With cannabis, officials wanted a reason to detain and deport as many Mexicans as possible.

Widescale job loss during the Great Depression of 1929 to 1933 made Americans resent the new migrants and their “evil weed” even more, and dozens of states decided to ban the plant altogether. The government’s way of controlling people by stereotyping their habits was successful, and it turned into a national strategy for keeping minority groups on a tight leash.

Harry Anslinger, first chief of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, offered the government’s view of the plant with one infamous quote:

“There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the U.S., and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers,” Anslinger said in the early 1930s. “Their Satanic music, jazz and swing, results from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers, and others.”

That image became the backdrop for a nationwide cannabis ban in 1937. Congress replaced that ban in 1970 with a law ranking illegal substances, and cannabis ended up in Schedule 1— the category for the most dangerous drugs with “no accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.”

In just a few decades, marijuana had gone from a popular medicine to a street drug with no medical value, according to U.S. law. It was like saying popular medicines Advil and Tylenol were all of a sudden as harmful as LSD or heroin — just because Mexicans used them.

Thankfully, the next generation knew better. And now, many Hispanic Americans are successfully advocating to rewrite the country’s wrongdoings.

Read Also: Cannabis Activists/Advocates

Latino Entrepreneurs Emerge After Legalization

The stigma against marijuana undoubtedly still exists, despite nearly every state decriminalizing small amounts of it and 18 states permitting full-scale retail sales for adults over 21 years of age. The wiggle room brought by legalization has naturally allowed several Hispanic entrepreneurs and activists to carve a niche in the fledgling industry. For countless more in the Latino community, legal cannabis has offered hope for the future.

Chanda Macias spent over eight years researching cancer as a student at Howard University in Washington D.C. Macias is a woman of Hispanic and African American descent, and has witnessed first-hand the tall barriers that people in each of those demographics face when trying to enter the industry.

“I’d always been a biomedical researcher and I found that cannabis was a therapeutic benefit for patients with cancer,” Macias said. “But unfortunately my advisors and educators told me ‘we don’t want you to study cannabis – it’s illegal and it’s had a harmful impact on the African American community.’ They wanted me to go in another direction.”

Macias wouldn’t be deterred, though. When her home state of Louisiana legalized medical cannabis in 2015, she opened Ilera Holistic Healthcare and began offering a variety of THC and CBD products for patients suffering from a gamut of illnesses — anxiety, pain and insomnia — as well as chronic conditions like cancer, seizures, and even autism. Macias now oversees dozens of employees and has an exclusive partnership with Louisiana-based Southern University to grow and research the plant. Her cannabis partnership with Southern is one of just two such deals in the entire country between a private cannabis company and a U.S. university.

Macias’ activism extends nationwide via Women Grow, an organization she was an early member of and is now the CEO for. Macias said being involved with the group, which is now over 50,000 members, has not only connected her with more Hispanic and African American women in the cannabis space, but also opened her eyes even wider to the plant’s enormous medical potential.

“It’s a natural ingredient that really restores what our cell-cycling system is supposed to look like,” she said. “I’ve met many women who have become medical refugees – meaning their children had to go to other states to use medical cannabis because it wasn’t legal where they lived.”

Cindy Ortiz, president of New Jersey-based Bloom Wellness, is also a Latina canna-businesswoman and original member of Women Grow. Ortiz, like Macias, became intrigued with the plant after witnessing first-hand its medical value.

Ortiz was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2016 and began struggling with pain, nausea, and lack of appetite. When a fellow patient introduced her New Jersey’s medical marijuana program, she found a more normal life amidst the chaotic and stressful chemotherapy regimen she was undergoing.

Her life-saving experience with the plant inspired her to open a dispensary, but getting there wasn’t easy. Besides overcoming funding hurdles, she felt she was stigmatized as a woman, mother and Latina trying to make it in the industry.

“I would say to vet anyone offering their services very carefully,” she advised. “Take the time and do some research, ask for references. There are a lot of people out there looking to make a buck but won’t deliver. More so if they see a Latin woman and stereotypes kick in.”

Florida-based Dr. Joseph Rosado, of Puerto Rican descent, lays claim to being the first doctor in the Sunshine State to recommend cannabis for an adult patient, a 35-year-old with a Stage 3 cancerous brain tumor. He’s also the first doctor to advise the plant for a child patient, a 15-year-old with a Stage 4 neck tumor.

Rosado believes the endocannabinoid system is “influential” in helping patients manage stress. He believes so much in the plant, he helped launch MarijuanaDoctors.com, a comprehensive website that helps patients book real doctors willing to recommend marijuana for treatment.

He is also an executive with the national non-profit Minorities for Medical Marijuana, which provides advocacy, education and training for minorities who have a vested interested in cannabis. He claims the lack of public education on cannabis has not only contributed to minorities’ struggle to enter the industry but also prevented millions of patients from receiving proper medical care.

“The first image many people have with cannabis is somebody with dreadlocks in a tie-dye shirt smoking a joint or sucking on a bong,” Rosado said. “They don’t see my typical five or six year old that was on five different epileptic drugs and was having 300 seizures a day, but is now just having five seizures per month with cannabis.”

For other Hispanic business owners, working in cannabis has offered a much-needed shot at opportunity.

Back in 2016, William Zitser was recently widowed, jobless, and deeply depressed. He went on a vacation to a friend in Ecuador to cheer up, and the trip turned into a sabbatical across cacao farms in Latin America, learning about the harvesting of hemp plants and how to make chocolate from it. Born and raised in Caracas, Zitser is a lifelong chocolate lover and was just starting to understand the benefits of cannabis.

“Back then, I was on antidepressants,” he explained. “At some point, I wanted to find something more natural. Cannabis helped a lot, but I’m not a productive smoker and it was making my workday difficult. So I tried CBD and it really helped me.”

Five years later, Zitser runs a successful business that combines two of his favorite items: CBD and chocolate. Los Angeles and New York-based Flor de Maria, named after religious cult-hero Maria Lionza, combines organic hemp and with Venezuelan chocolate CBD edibles for a “quality and sustainable” product that’s sold online and in over 80 stores across the country. Flor de Maria makes its chocolate from the bean, and focuses more on sourcing than CBD dosing.

“I’m very rigorous about the ingredients I use,” Zitser said.

Social Equity Plans Offer Opportunity

History hasn’t been kind to Hispanic and Latinos involved in marijuana. But interviewed activists believe the future should offer more promise. Recent societal trends toward racial equality has encouraged lawmakers to incorporate social equity initiatives in the cannabis industry, too.

New recreational cannabis laws in Connecticut, Virginia, New Jersey, and New York have acknowledged that cannabis prohibition disproportionately harmed minority communities in the 1900s and early 2000s. In response, the states designed their marijuana legalization laws passed this year to specifically empower minority communities, including Hispanics.

More than half of the 37 states and U.S. territories in which some form of the cannabis plant is legal have now incorporated social equity policies to level the playing field, according to a report from the Washington D.C.-based Brookings Institution.

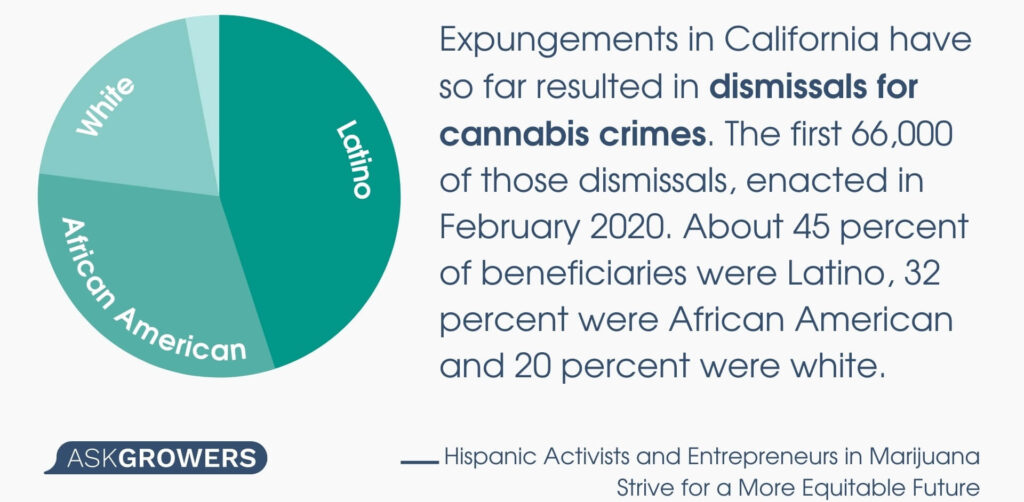

The policies mostly began with the dismissing of previous convictions related to possession and use of the plant, which meant anyone who spent time in jail for cannabis crimes no longer illegal under a state’s current laws could have their old cases dismissed. They’ll never get back the time spent in jail, of course, but expunging marijuana crimes from criminal records can help with everything from getting a job to buying a house, Macias said.

“Many of these people were trailblazers who made the end of prohibition possible,” she said. “They’ve suffered for decades as a result.”

Expungements in California have so far resulted in about 124,000 dismissals for cannabis crimes dating back as far as 1961, according to a CNN report. The first 66,000 of those dismissals, enacted in February 2020, saw almost half benefit Hispanic people. About 45 percent of beneficiaries were Latino, 32 percent were African American and 20 percent were white.

Similarly in New York, over 150,000 people with cannabis-related convictions have seen their convictions dismissed since 2019. Senate Bill S6579A called for anyone charged with possession of less than two ounces of the plant to have record of that crime expunged.

The expungement policies are specifically set out to assist minorities, who according to the American Civil Liberties Union citing data from police agencies across the country, had higher chances of being jailed than Caucasian people in every single state. So far, Macias said, the policies have offered “long overdue” relief.

“You’re talking about people who have been denied for jobs, passed on for loans and all kinds of other things just for using a plant that’s now legal,” she said. “The struggle that a lot of these trailblazers have gone through is unfathomable, and retroactively absolving these convictions is the least we can do. It’s just the first step.”

The next steps extend far beyond criminal justice. They incorporate real economic opportunity, in the form of preferential policies for business ownership.

A recently passed law in Nevada allowing up to 70 cannabis consumption lounges to open across the state requires that social equity applicants receive at least half of the business permits. Preliminary regulations from the state’s Cannabis Compliance Board defines social equity applicants as ethnic minorities, residents of neighborhoods in traditionally marginalized zip codes, or a person or relatives of a person who has spent time in jail for using the plant. Clark County, which includes Las Vegas and more than two-thirds of the state’s inhabitants, has a minority-majority population with nearly one-third of all residents being Hispanic or Latino compared to about 13 percent black and 11 percent Asian or Pacific Islander. That means the state’s social equity laws are more likely to benefit Hispanics than any other racial minority.

The Nevada lounge applicants will also save handsomely on the state’s hefty application fees and proof-of-capital requirements: they must show only $10,000 in capital, compared to $100,000 for non-social equity candidates.

In New York, the Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act, calls for at least half of all new adult-use marijuana licenses to be allocated to minority owners, which it defines to include women, Latinos and other people of color, as well as distressed farmers and service-disabled military veterans. Ditto for Connecticut’s new rec law, which mandates the same breakdown of licenses for social equity applicants.

Other states with marijuana social equity policies include California, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia.

The programs’ policies vary from state to state. California, for example, offers financial support and training to minority cannabis business owners. Other states offer no such process, but many have placed limits on the application process to give minorities better chances to win licenses.

And it’s not just states trying to diversify the industry. The city of Detroit attempted to set aside half of its licenses for longtime residents of the city, called "Detroit Legacy" applicants. It combined the residency requirement with proof of being impacted by marijuana prohibition, but the measure was stalled in court over the summer.

Such measures stand to benefit Latino cannabis entrepreneurs like Carolina Vazquez Mitchell and her California-based cannabis brand Dreamt, which specializes in sleep products.

Hurt by federal tax laws that charge cannabis companies almost double the annual duties of non-marijuana businesses each year, Vazquez Mitchell said access to the industry and funding are among the largest challenges Latinas in the industry must overcome.

“I think there are always challenges being an immigrant woman of color and running your own business, particularly if that business intersects with science, which is extremely male-dominated and with very few Latinas,” Vazquez Mitchell said. “We’ve seen other companies almost always run by white men with less impressive sales and pretty average products get very easy access to funding, while we have to show enormous traction before people believe in us.”

Read Also: Grower Stories #129: Aya Maria

Reinvestment Could Bring Meaningful Impact

Beyond clearing criminal records and opening the door to business opportunities, the social equity policies fulfill reinvesting in the minority communities — many of them predominantly Hispanic — that need the money most.

The exorbitant tax revenues raised by the plant means more money for local schools and libraries, revamped public areas like parks and community centers, and funds for drug rehabilitation programs.

The money is theoretically set to help rebuild communities affected by cannabis prohibition. Because cannabis hasn’t been legal, advocates argue more people in turn used other more addictive substances. The federal government and several states for decades offered lesser charges for crimes involving other popular street substances, such as cocaine and methamphetamines, because the latter drugs are federally classified as Schedule 2 instead of Schedule 1.

In Nevada, cannabis legalization has led to over $150 million in tax revenue issued to public schools. Nearly half of the state’s students enrolled in public education are Hispanic, according to the Nevada Department of Education. Another $600 million in California has gone to anti-drug programs targeting youth, per the Motley Fool, and Oregon has allocated upwards of $80 million to mental health and drug addiction treatment services.

It’s important to note that while the idea of purely equitable cannabis programs sound wonderful, the reality so far has suggested that successfully implementing them can be challenging. A 2019 report from Crain’s Chicago found that nearly every state in which social equity laws had been proposed had yet to meet expectations. The article suggested that a mix of controversy, corruption, ineptitude and just plain greed had contributed to underwhelming programs in California, Colorado, Massachusetts and Oregon prior to social equity gaining more widespread national traction in 2020. White men still owned the vast majority of cannabis businesses in each of those states, and the percentage of minority owners had not significantly increased during multiple years of legal marijuana in those states.

In the meantime, Hispanic people leading cannabis businesses are taking matters to diversity the industry into their own hands.

Miriam Aristy-Farer started Herbas in her kitchen, experimenting with herbs she had grown that had anti-inflammatory and calming effects. Aristy-Farer experimented one day in 2016, adding drops of CBD oil to the herbs and realized it had an even improved effect.

Five years later, her West Harlem-based brand in New York City has committed to bringing her lifestyle to the Hispanic community with affordable prices and bilingual labeling. Herbas supports local hemp farmers and hires Hispanic employees to put diversity in action.

“It’s more than Black owned businesses. It’s Latino, women, Asian and Muslim,” Aristy Farer said. “We want everyone to heal naturally and have access to exceptional quality, farm direct products.”

Karina Primelles, who moved to Southern Oregon from Mexico City, has brought a similar impact. She and her business partner Mennlay Golokeh Aggrey co-founded CBD brand Xula last year, making the new company one of the few in the industry to be Latina and Black-owned. Xula grows its own hemp and develops products targeting customers struggling with symptoms of anxiety, menopause, menstrual cramps and insomnia.

Karina Primelles, who moved to Southern Oregon from Mexico City, has brought a similar impact. She and her business partner Mennlay Golokeh Aggrey co-founded CBD brand Xula last year, making the new company one of the few in the industry to be Latina and Black-owned. Xula grows its own hemp and develops products targeting customers struggling with symptoms of anxiety, menopause, menstrual cramps and insomnia.

Just as importantly, Primelles and Aggrey are heavily involved in the Floret Coalition, an anti-racism collective of small businesses in the cannabis industry that support and fund equity-oriented actions through monthly donations and social campaigns.

Together, Xula and 130 other brands in the Floret Coalition have helped raise $70,000 and awareness for organizations that prioritize the needs of Black, Latino, and Indigenous communities.

“As women who split our time in the U.S. and Mexico, we recognized that both spaces lacked CBD products specifically targeted to nurture our bodies—bodies with wombs,” Primelles said. “The grave lack of representation of Latina and Black people like us in the industry, both as executives and customers, also galvanized us to build something not just for us, but for our communities.”

Educate, Implement and Legalize

As with the lion’s share of conflicts in the legal marijuana industry, many barriers to entry faced by Hispanics could be knocked down through federal legalization. Removing the plant from the U.S. DEA’s Schedule 1 list would open the door for banking while increasing access to capital loans and investment — both of which Latinos have struggled to obtain at the same rates as Caucasian entrepreneurs in cannabis.

An increasing number of advocates are skeptical that the end of nationwide prohibition is coming soon, though. Despite a handful of bills circulating through Congress in recent years such as the SAFE Banking Act, the STATES Act, and the MORE Act, elected officials have not made significant progress toward federal legalization for the near future. That’s just fine for Macias and Vasquez Mitchell, who argue the industry should work on implementing social equity and justice initiatives before making cannabis an open-market free-for-all.

“Those issues need to be resolved before we open legalization to all,” Macias said. “Expungement of records and release of people that had non-violent cannabis possessions should be dealt with. If we legalize too fast, these people might be left behind, and it’s my goal to make sure we do it with the right steps at the right time.”

“There’s always a lot of talk about making the industry more diverse and helping companies founded by people of color,” Vazquez Mitchell added. “But most of it leads nowhere and the opportunities tend to stay with those at the top.”

Interviewed Hispanic canna-preneurs asserted that properly educating university students about the plant would significantly improve opportunities to get involved in the industry. Per Rosado, less than 10 of U.S. medical schools currently offer programs exploring the endocannabinoid system, leaving many doctors clueless when approached by patients for cannabis-related advice. Destigmatizing the plant though proper education would encourage more Americans, especially those in elite medical professions, to recommend or at least consider it for their patients.

Doing so, in turn, would help eradicate stereotypes against Latinos and other minorities who have been associated with the plant and jailed for using it during a century of injustice, Rosado said.

“The government hasn’t educated us besides lies and myths,” he said. “For now, it’s still up to us to educate and inform ourselves. And it’s very important that we do that”

References

https://drugpolicy.org/blog/how-did-marijuana-become-illegal-first-place

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/dope/etc/cron.html

https://www.enjoyflordemaria.com/

https://www.cnn.com/2021/09/28/us/marijuana-convictions-los-angeles-county/index.html

https://www.cnn.com/2019/08/28/politics/new-york-marijuana-convictions-expunged-trnd

https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2019/s6579

https://www.aclu.org/gallery/marijuana-arrests-numbers

https://www.leg.state.nv.us/Division/Research/Districts/Reapp/2021/demographic-data

https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2021/S854

https://www.freep.com/story/news/marijuana/2021/06/17/detroit-recreational-marijuana-law/7616907002/

https://doe.nv.gov/DataCenter/Enrollment/

https://www.fool.com/research/marijuana-tax-revenue-by-state/

https://www.chicagobusiness.com/crains-forum-cannabis/across-us-visions-cannabis-equity-come-short

https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1996

https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/3032/all-info

https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/3617/cosponsors?pageSort=lastToFirst

Industry

Industry

.jpg)

(1).png)

Be the first and share your opinion

Write a Review